By: Charles Q. Choi, OurAmazingPlanet Contributor

Published: 10/08/2012 12:35 PM EDT on OurAmazingPlanet

Published: 10/08/2012 12:35 PM EDT on OurAmazingPlanet

The entire outermost part of Earth may be wandering over the planet's whirling molten core, new research suggests.

Knowing whether the Earth's outer layers

are roaming in this manner is key to understanding the big picture of

how the planet's surface is evolving overall, scientists added.

At various times in Earth's history, the planet's solid exterior — its

crust and mantle layers — has apparently drifted over the planet's

spinning core. To picture this, imagine that a peach's flesh somehow

became detached from a peach's pit and was free to move about over it.

This movement of the Earth's outer layers is known as "true polar

wander." It differs from the motion of the individual tectonic plates

making up Earth's crust, known as tectonic drift, or the motions of

Earth's magnetic pole, called apparent polar wander.

'Hot spot' landmarks

Past research suggested the Earth experienced true polar wander during

the early Cretaceous period that lasted from 100 million to 120 million

years ago. Determining when, in which direction and at what rate true

polar wander is taking place depends on having stable landmarks against

which one can observe the motion of Earth's outer shell, much like one

can tell a cloud is moving by seeing if its position has changed

relative to its surroundings.

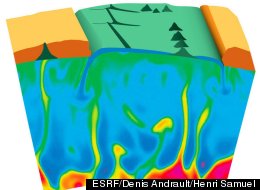

Volcanic "hot spots,"

or areas of recurrent volcanism, are one potential landmark. Geologists

have suggested these are created by mantle plumes, giant jets of hot

rock buoying straight upward from near the Earth's core. Mantle plumes

are thought to create long island chains such as the Hawaiian Islands as

they sear tectonic plates drifting overhead.

Scientists have

treated hot spots as stationary features for decades. The idea was that

material surrounding the mantle plumes roil about to form structures

known as convection cells that kept the plumes straight and fixed in

place. [50 Amazing Volcano Facts]

Later on, however, researchers began suggesting that mantle plumes

could move about slightly, caught as they are in the flowing mantle

layer under the crust. "From this point of view, the plumes are expected

to move, bend and get distorted by the 'mantle wind,' resulting in hot spot drift over geologic time," said researcher Pavel Doubrovine, a geophysicist at the University of Oslo in Norway.

By allowing hot spot positions to meander slowly, Doubrovine and his

colleagues have devised computer simulations that better match

observations of the chains of islands created by each hot spot.

"Estimating hot spot drift in the geological past is not a trivial

task," Doubrovine told OurAmazingPlanet. "It requires substantial

modeling efforts."

The scientists then compared the way the

Earth's outermost layers drifted in relation to the planet's axis of

spin. The Earth's magnetic field is aligned with the core's axis of

rotation, and researchers can tell how Earth's magnetic field was

oriented in the past by analyzing ancient rock. Magnetic minerals in

molten rock can behave like compasses, aligning with Earth's magnetic field lines, an orientation that gets frozen in place once the rock solidifies.

Current wandering

Using their simulations and the magnetic field rock record, the

scientists identified three new potential instances of true polar wander

over the past 90 million years. These include two cases in which the

Earth's solid outermost layers traveled back and forth by nearly 9

degrees off Earth's axis of spin

from 40 million to 90 million years ago. Moreover, the researchers

suggest that Earth's outer shell has been undergoing true polar wander

for the past 40 million years, slowly rotating at a rate of 0.2 degrees

every million years.

Researchers suspect true polar wander is

caused by shifting of matter within the mantle, due, for instance, to

variations in temperature and composition. However, "we don't know yet

what specific tectonic events may have triggered the specific episodes

of true polar wander that we identified," Doubrovine said.

These

new details regarding true polar wander could help shed light on what

triggers it. In the future, the researchers plan to look even further in

the past at how the planet's outermost layers have changed. Doubrovine

and his colleagues Bernhard Steinberger and Trond Torsvik detailed their

findings online Sept. 11 in the Journal of Geophysical Research — Solid

Earth.

from: Huffington Post